Research with Young People

The Seen and Heard academic team has adopted a rigorous mixed-method study in which quantitative and qualitative data are collected simultaneously in Malta, Wroclaw and Berlin, to establish young people’s understanding and experience of freedom of expression, in Europe.

For maximum objectivity and rigour, our research combines a comprehensive suite of qualitative research methodologies supported by extensive quantitative research involving the participation of over 500 students in all three participating countries, aged 10-14.

The Process so Far

- human rights education as a method of promoting youth participatory citizenship

- artography as a method of understanding protest and freedom of expression to

- methodology based on care and intergenerational solidarity

- co-curating protest with young people transmedially and cross-sectorally.

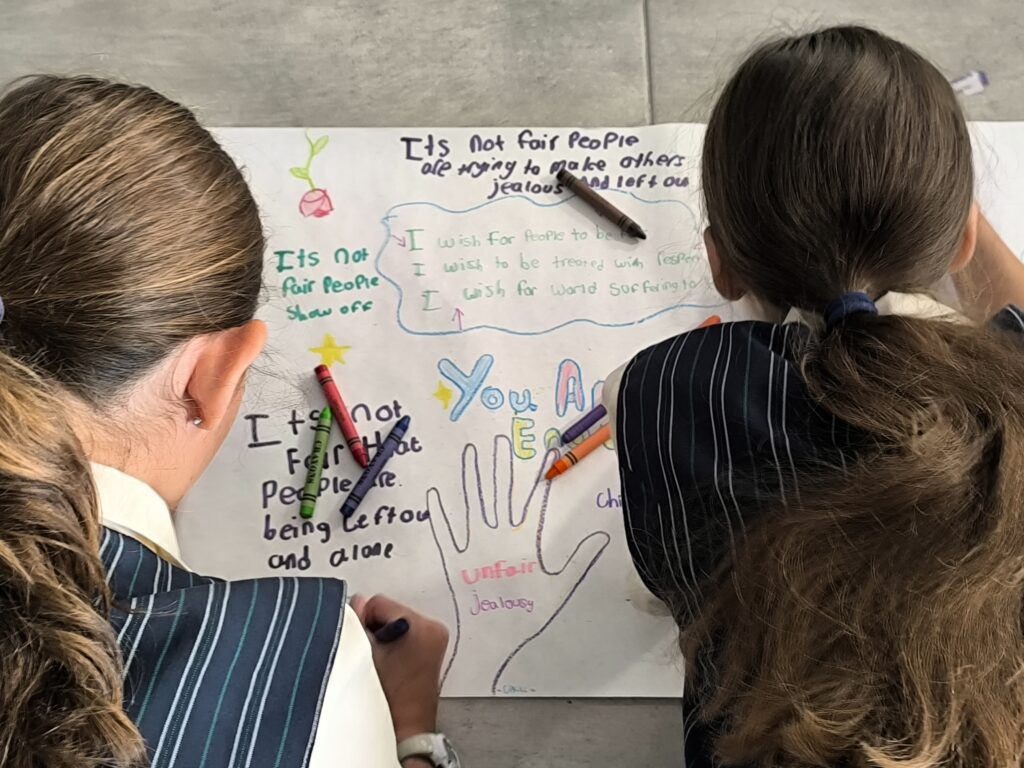

Using the idea of ‘creative protest’ as a basis for social change, the project places youth at risk of marginalisation and exclusion, at the centre of political dialogue through blended learning experiences and sustained support from researchers, educators, artists, activists, publishers, and policy makers.

The project develops in three phases across three countries; research on human rights with 10 to 14-year-old children in schools, a freedom of expression and creative protest mentoring programme, and the launch of a social movement.

While working with the participants, researchers are mentoring the young people to understand better how stories and storytelling can help them express themselves as they speak out about matters that are important to them.

Adopting a methodology of care, alongside that of artography, the interdisciplinary team is keen to ensure that we reciprocate the learning we receive from our data collection with the children involved.

They will receive updates on the research results, as well as human rights training. Additionally, they will be invited to participate in creative protest illustration workshops with visual artists, including award-winning illustrator Chris Riddell, and communal dreaming and writing workshops with the author, Sita Brahmachari, among others.

Groups of children from across the three countries will also join mentoring programmes that allow them to produce protest videos alongside established filmmakers Charlie Cauchi, Uli Decker, and others.

The views and experiences of children are the core consideration of the project and are placed at the forefront of all its processes throughout. Indeed, they never fail to inspire and surprise us, and we are keen to discover what more they have to say!

COUNTRY-BY-COUNTRY RESEARCH

Malta

The Malta team of researchers, led by Dr Giuliana Fenech, are running the survey across state, church, and private schools in a bid to involve as many children as possible in a representative way.

Research Support Officer, Sandy Calleja Portelli, visits schools each week taking the time to explain the scope of the survey and running a literature workshop.

During this workshop, the children have the opportunity to explore books that feature social justice stories and young people speaking up on important social issues.

“Working with children is also about understanding their daily lives and the contexts in which they learn, play, and grow. This project is about pausing adult expectations to really take the time to listen to the children. It’s also about reaching out to those at risk of marginalisation to make sure that they too feel seen and heard”, says Sandy. “We have been amazed by the young people’s responses, the depth with which they engage with the literature and their insightful comments.”

Overwhelmingly, students value being part of a study ‘that is not only happening in Malta’, and many tell us that this is the first time they have been asked to reflect on these issues so deeply. As one student said: ‘I feel respected, nobody has ever asked me these things before’. Most importantly, the children are clearly enjoying the sessions, saying ‘it’s a fun way to read a book … doing more than just reading the words’. Another told us, ‘I wasn’t going to take part, but my friends said it’s fun so…’.

It’s not just the children who are commenting on the need of projects like this. The educators in all the schools we are visiting have pointed out that the importance of instilling courage and confidence to speak out in their students is amplified in a world of social media and fake news. It is only through collaboration across all stakeholders, and the resourcing of schools, that we ensure that young people feel seen and heard, and truly acknowledged as citizens with agency.

Berlin, Germany

The German research team, led by Dr Farriba Schulz, and supported by Lena Meidinger, Leah Ilk and Laura Kirschstein, was running online surveys and literature workshops in two primary schools in two 6th and one 5th grade class in Berlin.

But before they started, the students drew a card from a set of footballers and women of influence and used their names as their pseudonym. Choosing a pseudonym not only guaranteed anonymity, but also led to extensive discussions at the beginning of the programme, which already concerned the children’s right to privacy. This showed the primary student’s considerable knowledge about data protection and ways to protect privacy on the Internet, such as the use of passwords and pseudonyms, and offered the opportunity to talk about how we would continue to work with their information and why their information is so important to us.

However, the most interesting discussions took place during the literary workshops. In order to lead the discussion, questions they were asked were for instance: “What comes to your mind when we say play? While they frequently mentioned a lot of video games like Fortnite, Minecraft and FIFA in relation to the term “play”, sports such as soccer or basketball as well as role-playing or board games were mentioned much less frequently. Surprisingly, this applied to all the classes in which the team did the workshop. The research team also asked the participants about environment, safety, protest and freedom. And here alone, the children’s knowledge and diversity in their answers was outstanding. It was great to see that the students extensively commented on and discussed all the terms. The students spoke of CO2, nature, family, community, safe home, a door you can lock, no war is freedom etc.

In order to intensify this collection of associations, the team then defined a few selected children’s rights together with them and deepened these reflections by looking on children’s and human rights addressed in children’s literature. But before the students picked a picture book of their liking, together we watched the wordless animated short film “A Joy Story: Joy and Heron” by Kyra Buschor, Constantin Paeplow and Kenneth Kuan (AUS: 2018) together, while focusing on which human rights/children’s rights could be identified and why. According to the story, in which a bird steals from a fisherman for his young one’s worms, a small discussion arose about whether and when theft is legitimate and who is responsible for the care of children. Such small but important thought experiments occurred during the contemplation and discussions on and about the books in relation to many different human rights/child rights addressed in the books and will hopefully be continued further.

Wroclaw, Poland

The UWr team, led by Dr. Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak, has recently finished the first stage of the mentorship programme, which involved collaboration with Polish and Ukrainian students and teachers at Primary School No. 1 in Wrocław.

This stage consisted of four steps: a questionnaire for the students before the workshop, the workshop “Can Literature Inspire Us to Act?”, a questionnaire for the students after the workshop, and interviews with the teachers. Both questionnaires were designed by the consortium, with some variations due to language issues, cultural contexts, and suggestions from ethics committees at the partner universities.

The first questionnaire addressed, among others, the children’s knowledge of their rights and the themes they consider important in books, movies, or games.

The second one was designed to find out whether the workshop had a positive impact on the children’s attitudes toward these issues

Moreover, after the workshop, Dr. Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak and Dr. Mateusz Świetlicki interviewed Ms. Katarzyna Zwierzyńska-Paluszek and Ms. Yuliia Solomentseva, the teachers involved in the project.

We are now analyzing the data collected through the questionnaires, interviews, and the workshop.

Collective report

This report presents the findings of Work Package Two of the Seen & Heard project, which explored how children in Malta, Berlin, and Wrocław understand and experience freedom of expression and other rights through surveys and literature-based workshops.

By analyzing the child participants’ engagement with stories and rights-related themes, the research offers valuable insights to educators, cultural institutions, and policymakers committed to fostering inclusive and participatory environments for children.

Contemporary Social Movements

The Seen and Heard project developed the full life-cycle of a social movement co-created with young people in post-migrant schools and communities.

Our research and the implementation of our mentoring programmes have yielded inspiring results on how the process can be replicated to benefit more young people and their caregivers.

A publication outlining our social movement and methods in more detail will be uploaded in 2026.

Research publications

Emerging from the Seen and Heard project are a number of publications that feature research results on different aspects of the process.

We are open to collaboration with other academics working in the same field and look forward to hearing from you if our research interests align.

For details of forthcoming publications, click on any of the links below.

Read more aBout each publication

The Seen and Heard Project as a Case Study in Children’s Social Movement Praxis

Forthcoming

In the post-digital age, where digital technologies are deeply integrated into everyday life and modes of political participation, children’s roles in social movements demand urgent re-theorization.

This paper advances the concept of ‘storied citizenship’—a form of civic engagement rooted in narrative practices—through video-based expression, including communal writing, participatory animation, and performance workshops.

In the project Seen and Heard: Young People’s Voices and Freedom of Expression, storytelling becomes platformed activism, creating a transmedia movement space where aesthetic production and civic identity-making coalesce.

Operating interactively across generations, institutions, and cultural contexts, it constructively frames children not as passive recipients but as co-authors of public discourse living in a highly diverse Europe. Children’s multimodal storytelling—particularly in post-migrant and multilingual classrooms—offers embodied insight into how civic identity is felt, explored, and gradually performed through speech, art, and metaphor.

In this chapter, we use Dieter Rucht’s interactionist, constructionist, and process-oriented framework to analyze Seen and Heard as a dynamic social movement structure full of purposive action (Merton 1968) and consider Johanna Leinius’s concept of cosmopolitical solidarity to illuminate the young people’s experience. Here, children narrate experiences not merely for catharsis or classroom engagement, but to do something—to advocate, express, resist, and participate meaningfully in public life.

Communicating through visual art, communal poetry, and video performance in ways that subvert traditional expectations of protest and persuasion, the Seen and Heard young people affirm storied citizenship as a legitimate, complex form of youth activism in the post-digital era.

They challenge adultist assumptions about who may speak and act politically, proposing a model of movement-making grounded in rights, recognition, solidarity, and imagination.

Co-Creating Change with Young People through Children's Literature and Art in the Seen and Heard Project

Forthcoming

Associated most strongly with the future, young people are often positioned as placeholders of hope and action.

Little regard is given to their geopolitical context and individual socio-cultural landscape because retaining our image of them as innocent and pure, as well as cognisant and able to solve issues that we, as grown-ups, have failed to fix is more important. For two reasons.

If young people are not able to fix the world, we are doomed. If young people are the present rather than the future, the doom is not even forthcoming, it is here already. That is a depressing thought.

Depressing or not, it’s crucial that we come to terms with it. Only by embracing the complexity of this generation’s lived experience in the world today can we truly begin co-creating the resourcing that is necessary to change things.

Young people’s present is full of seeming contradictions. They live embodied and digital lives making them hybrids, their positioning is both local and global so they’re glocal. Often they feel engaged and distanced at the same time as the internet bombards them with information, allowing them to turn their back on it almost instantaneously. In many contexts they are positioned as learners even though they have the potential to be teachers if given enough space and trust to explore, experiment, and put their ideas into practice.

Whether living in a peaceful society and planning for their adult life, or living in war-torn countries and fighting for survival, young people have a lot to offer. This article explores the opportunities and challenges inherent in mobilising young people to act within value-based social movements. Its framework rests on four core pillars; movement building, social justice, children’s rights and participatory ethics.

It draws on ideas from children’s literature, critical childhood studies, decolonial theory, feminist ethics of care, sociological theory, and human rights practice

Entanglements of Children's Literature, Creativity and Research in the Seen and Heard Project

Forthcoming

This article, grounded in the Seen and Heard: Young People’s Voices and Freedom of Expression project (2023–2026), explores how children’s literature research can be reimagined as a relational, affective, and material practice that supports children’s agency, rights, and co-creation of knowledge.

Drawing on feminist new materialism, the authors challenge traditional, adult-centric approaches to children’s literature and research. Instead of treating books as fixed texts and children as recipients, the article conceptualizes both as part of dynamic assemblages—constellations of human and more-than-human forces, including bodies, spaces, objects, affects, and institutions.

The article proposes to see reading as a practice that moves beyond decoding texts to inhabiting them through embodied, affective, and relational engagements. Reading becomes an event, a moment of becoming-with, not a solitary act of interpretation.

Children’s responses to books like Shaun Tan’s Cicada or Amanda Gorman’s Change Sings are not treated as data points but as “glowing moments” (MacLure, 2013)—affective intensities that reveal how children’s lifeworlds are entangled with literature, space, and social structures.

This shift allows for a more expansive understanding of childhood and adulthood as co-creative, intergenerational, and more-than-human conditions. It also aligns with the ethics of care, where research is not done on or for children, but with them, in shared spaces of inquiry and transformation.

Methodologically, the article highlights iterative, open-ended, and care-full practices that led to the emergence of intra-activist assemblages—spaces where children could explore difficult topics like exclusion, bullying, racism, and ethnic discrimination through play, improvisation, and dialogue.

The concept of minor gestures (Manning, 2016) is central: small, often unnoticed actions that carry the potential for ethical and political transformation.

The article concludes by reflecting on the implications of this work for children’s literature. It calls for a shift from representational to relational thinking, from adult authority to intergenerational collaboration, and from fixed categories to fluid, situated practices. Ultimately, it proposes that reading with children—rather than reading to or about them—can become a mode of living research.

Freedom of Expression in Literature, Media, Culture

Forthcoming

Initial research emerging from the Seen and Heard project shows that young people do care about human rights and have strong opinions about social and political issues that they understand impact their lives and the lives of those around them.

The Seen and Heard participants were invited to engage deeply with literature and art that features characters speaking up for themselves and seeking creative solutions to challenges that may, at first, seem hopeless.

The young people discussed the environment and climate crisis, gender inequality, fast fashion and damaging cultural trends, bullying, and child-adult relationships in which they often feel invisible. They enjoyed the interdisciplinary mentoring programme offered by the project because it gave them a safe space in which to think and learn about human rights and their own life experience. They also passionately engaged in the playfulness that making their own films from scratch entailed.

As part of our research in this project, we are interested in exploring the following questions: How does the right to participate manifest in opportunities for young people? What role does geopolitics play in the amount of freedom or restriction young people face in speaking up about matters that are important to them?

At a meta-level of research and practice, how can academics, artists, and activists reach young people to foster authentic spaces of co-creation? What are the challenges and opportunities embedded in participatory research with children? How does the complexity of co-creating human rights creative protest pieces manifest? Does working with schools help or hinder co-creation? How do literature and art offer insight into human rights and can they be tools that help young people’s voices to be heard?

We also research, write, and work alongside colleagues who are doing similar work with young people around the world. This volume will bring together all our insights and learning experiences.