Freedom of Expression Mentoring programme

Our mentoring programme adopts an artivist approach and is led by the academics and artists in each country, featuring guest appearances by award winning illustrator, Chris Riddell, and author and activist, Sita Brahmachari.

Together with the young participants in the programme, we co-create protest pieces that inspire social change.

The Power of Care-Full Activism

In this mentoring programme, we are drawing among other disciplines on a/r/tography, children’s literature and culture scholarship, and childhood studies to realize the following objectives:

- Co-production of creative protest and mobilization of the human right of freedom of expression WITH young people, considered as artists and makers in their own right.

- Design and implementation of a full life cycle of a social movement (from academic research to activist art, public dissemination and evaluation) in three European localities with a strong migrant, refugee, and asylum seeker population.

Understanding children's everyday realities

Throughout our process we “re-turn” to our data not so much only by reflecting on or going back to a past that was, as Karen Barad (2014: 168-187) puts it, but by turning the data “over and over again”, trying to create “thicker” understandings of children’s everyday realities that have emerged in the inter- and intragenerational explorations of what it means to children to be seen and heard in their schools, families, and societies. Although that was not our primary goal, some of these everyday contexts and experiences emerged in the participants’ responses to the children’s books they read with us and in the surveys we conducted, while some came up in our joint work on creative protest. In our analysis, we rely on the new materialist concepts of the assemblage and the event (e.g. Bennett 2010) in an attempt to remain attentive to how – as researchers – we were drawn into a unique relation with children’s lifeworlds. We suggest that such an attention in our research enables us to think of youth and adulthood beyond the logic of the child/adult binary and to appreciate how we are all fellow beings always in the process of changing with the world around us.

We began by asking children in all three countries what they thought freedom of expression means and how they relate to it in their own lives. We followed that up with literary workshops and a second survey. Over 600 young people aged between 10 and 14 of over 50 nationalities and many languages participated at the same time in Malta and Gozo, Wroclaw and Berlin. The report of this survey may be viewed here.

The workshops

The literary workshops took a slightly different approach in the three countries. In Malta the focus was on the discussion of who is given the power to speak and act in stories and whose perspective is left out. The Wroclaw workshop was dedicated to the question “Can literature inspire us to act?”, and the Berlin workshop asked which children’s and human rights are thematized in the books, how, and in what way. The students were invited to browse the book selection and choose one to explore in more depth. The complete list of books used in each country may be viewed here.

After the workshops, the children were invited to sign up for a mentoring programme aimed at supporting and accompanying them in developing a creative peaceful protest about issues that bother them the most and to be able to stand up for themselves and each other, in a safe and effective way. We chose to focus on film production because video is a popular form of education and entertainment for this demographic and also because it allows children to participate in different ways – behind the scenes and on centre stage.

Independent filmmakers Charlie Cauchi and Uli Decker were invited to lead this part of the mentoring programme, sharing knowledge on how to script, produce, film, and edit videos through a process of play, improvisation, and joy.

Children's Panels

Upon completion of the protest pieces, the children were invited to join panels run in each country to question grown-ups in positions of power about affecting change. The panel in Malta focused on representation in publishing and books, the panel in Wroclaw focused on children’s voices in human rights discussions, and the panel in Berlin [titled to be confirmed]. The panels may be viewed here.

Assemblages

When exploring the data from our project in relation to moments rooted in children’s everyday lives, it is helpful to turn to the new materialist concept of the assemblage, which highlights the fundamental relationality of all living beings, non-living matter, language, ideas, memories, dreams, experiences, events, spaces, affects, and more. Assemblages are open-ended networks of “connections, always in flux, always reassembling in different ways’ (Potts 19). An assemblage is made up of different elements that come together to create something more than the sum of its parts, while each part also exists beyond the assemblage itself. We can never fully know what an assemblage can do, as it is incessantly forming, undoing, and reforming (Fullagar and Taylor 2022). The assemblage thus challenges the idea that humans are always at the centre of meaning-making and creating relations (de la Cadena 291–292).

What may help us attend to the complexities of assemblages are events – moments when something becomes felt, visible, or known; when the energies of the assemblage come together. Events enable us to feel what others feel and sense as they interweave our bodies with other bodies, exposing our contemporaneous intersubjectivities. Also, while an event happens here and now, it also carries in itself both the past (it is connected with earlier events) and the future (it holds the promise of what might yet happen). Finally, an event cannot be pre-planned because we can never be certain how and what will emerge in its course. It re-composes situations and propels further events. Our responsibility as researchers is thus to be accountable for how and why our research is a boundary-drawing practice (Barad 140) through which we notice assemblages and events.

Our position is never neutral and the knowledge we produce is always situated and provisional. In what follows, we present three vignettes – reflective accounts of the workings of the project assemblages – that are especially significant to us individually as instances of the glowing data (MacLure 2013), that is the data that stands out and demands attention, even if we can’t quite say why. These moments—or “glows”—may not immediately make sense, but they point to something important happening within the research assemblage.

Vignette 1: Giuliana Fenech

Freedom of expression, EU funds, immigration, children, schools do not form an easy assemblage but for a project committed to reaching all children, irrespective of their cultural background and how long they had been in our countries, I believe it is an effective one. Two years in, what stays with me is the power of loving individuals within unloving systems (Seabrook 2025), especially when trust is developed over time.

We witnessed educators, children, artists, activists, academics coalesce around the child standing at the back of the room with tears rolling down her eyes because in the book A Child Like You, she had her first encounter with a literary heroine that looked like her. We applauded the boy who trembled to speak his name because of fear of the bullies that had dominated his life for years, taking control of the camera to plead to school administrations, stop bullying if you want to stop child suicide. There is a lot in the political context of our time that encourages us, pushes us even, to give up the fight for equal rights and freedom of expression. But, encountering these children and the educators alongside them, has given us much to think about and act upon. The data speaks clearly.

Part of the assemblage that envelops these migrant children (48 nationalities in one grade in one school among other phenomena that emerged from our research) are the gaps between the systemic and the individual. While 86.4% of educators believe that stories encourage young people to voice their opinions and are important, 63.8% felt that young people are “Rarely” or only “Sometimes” encouraged to speak up about social justice issues. Can a temporary project mobilise freedom of expression within this landscape? On 8th March 2024, the Malta research team arrived at St Albert the Great College to run one of our workshops. Sandy Calleja Portelli explained the nature of the project to the students, including their right to ask any question they like or withdraw from the project, at any time. The team had been preparing to run these workshops for over a year. Everything was meticulously planned to engage the students’ attention and ensure it was a fulfilling experience for them.

Our attempts were successful. We did capture the students’ attention but not in the way that we envisioned. When the team entered the classroom, a student asked whether we were serious when we said that they could withdraw at any point, which Sandy confirmed as being correct. One by one, the students asked to withdraw their participation until only three remained. At this point, the Head of School addressed the students explaining the effort that the school’s administration and research team had made in order to schedule the sessions for the students’ benefit. He highlighted how rare it is for young people to be invited to make their voices heard in academic research but reiterated the commitment to allow students to choose whether or not to participate. In order to ensure students did not feel pressured to participate, he then asked students to make their final choice and left the room. They didn’t change their minds. Sandy completed the workshop with the three remaining students and had only their and her own reflections to report back from this workshop. Our initial dismay slowly morphed into reflection and even satisfaction. Rights education indeed, only made possible because the assemblage of freedom of expression, EU funds, immigration, children, schools also included care, honesty, and reciprocity. These ‘glowing’ moments are not only part of the Malta experience. They’re project wide.

Vignette 2: by Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak

Two events from the project in Wrocław have stayed with me with exceptional emotional clarity – so much so that I recall being moved to the verge of tears – tears of joy and awe. One participant who took part in all the stages, stood out for her decisiveness and confidence and dominated the group sometimes. She happened to be a member of the group I mentored. On two occasions when we needed to move around the school, I noticed how (1) she stopped a young boy on his way out of the school, put his hood on (it was a chilly day) and asked him if all was ok; (2) a younger girl ran up to her and hugged her tightly as they talked about the younger girl’s classes.

Although I hesitated as I did not want to be too inquisitive, I did ask her later about those two encounters. She explained briefly that the older students volunteered to look out for the younger ones and help them at school. I was moved by the kindness, care and even tenderness with which the participant approached her younger peers and wondered how much we all need such small gestures in our lives – schools, workplaces, homes… To me, in these fleeting interactions, care and solidarity were not abstract principles but active forces—affective intensities emerging from the relational field between bodies, institutional structures, the atmosphere of the school, the chill in the air. They were a subtle, quiet, even instinctive, and yet so powerful and tangible embodiment of a lived understanding of human and children’s rights and an ethics of responsibility and relational solidarity, which matter so much to us in the project on various levels.

I realized then that solidarity and social mobilization do not necessarily happen only through large collective actions but also, and maybe primarily, through everyday micro-practices. I also liked how the school intentionally structured and cultivated opportunities for older students to look after the younger ones and to model care-full behaviours so that later they would be practised by the younger students as well. This event—the stopping, the hood being pulled up, the hug—is a crystallisation of this assemblage’s potential. It emerged through the interplay of human and more-than-human forces and carried forward the momentum for further events, new attachments, and new lines of thought, including my own.

These affective / affectionate gestures I witnessed have stayed with me not because they offer a clear data point, but because they glow (MacLure 2013). They tug at me still, pushing me to reflect on the narratives we construct about children in our project: How do we attend to their capacities to care, to lead, to support others, and to express themselves that are already there – before we conduct our research, introduce and discuss children’s books, and mentor participants in creative protest? How can we remain aware of these capacities beyond the lifetime of the research? And, more generally, how do we appreciate childhoods as constantly evolving in ways that are both visible and invisible to the researcher?

Vignette 3: by Farriba Schulz

As the students involved in Berlin have stated on several occasions during the mentoring program, what they most wish for is to end war, no AFD (right wing party in Germany), no racism and no bullying). It is not surprising that one group chose bullying when looking for their film topic during the film workshop.

The students have had many experiences with racism and bullying, and not just during their time at school. Once again, it was an uncanny aha effect for me to see which factors and what significance central attachment figures can play in this. The discussion about the role of toxic masculinity in growing up, which has just been triggered in the UK by the TV series “Adolescence” (2025), and targets the relationship level alongside other important structural issues in capitalist patriarchy, comes to mind. When I think of my experience with the students in Berlin, I remember the incredibly approachable teacher who not only successfully addressed bullying and racism together with the students with the help of a multi-professional team over the last years, but also worked out strategies against it with them.

With our team of scientists, educators and artists, we joined a focus group of students who were already able to name their experiences very precisely and who knew and recognized discriminatory structures. This was also evident in the literature workshop and also in the artistic processing during the mentoring program.

When we look at the student’s reader responses in Berlin for example to Shaun Tan’s picturebook Cicada, the students not only addressed the children’s/human rights to „no discrimination“, to protection from violence or the right to food, clothing and a safe home, but referenced directly their everyday school life: one student said “I used to be bullied”, which directly links to what the students said the picturebook is about – namely “about exclusion and discrimination” that features “a cicada that is bullied because it is not human and looks different”.

Surprisingly, one student has linked their own school life experience with the discriminatory and exploitative working context of the cicada, when they wrote that the book is about “that he has no break and is not allowed to go to the toilet and his salary is deducted” While reflecting on this book, the student talked with a student assistant about the book and how the cicada was suppressed. The student has had the experience of not being allowed to go to the toilet in the school context, but said that children have the right to pursue a human need and considered whether this also applies to the cicada. The student and the student assistant thought about it together and answered the question in the affirmative. “I have to go to the loo now too, so it’s my right to go now!” the student said. The student assistant agreed and sent them to the loo The notes on the book and the dialogue directly link to what the students also answered in the surveys when asked what bothers them in their neighborhood, at school or in places they visit. Here you can find answers like “that I was excluded”, “That I am not allowed to speak Turkish freely at school”, “injustice” and “racism”.

Another student answered as follows “It bothers me that when I’m at school it feels like I’m in prison because we have to do things we don’t want to do or that we have to go to the yard at a certain time or that we only can eat at a certain time the teachers just have control over most of the kids I sometimes get degraded by my one teacher and then they wonder why we can’t focus at school it’s just bad”.

Vignettes: summary

The diverse vignettes we have shared are not just observations—they attempt to represent moments in the ongoing becoming of the research assemblage itself, entangled with our ethical commitments, methodological choices, and affective responses. They remind us that knowledge is not only what we extract or represent, but what we co-compose with the vibrant matter of the everyday. Re-turning to such moments asks something of us as researchers: How do we account for such subtle yet powerful affective intensities within the frameworks of research? How do we remain attuned to children’s capacities for care, leadership, and relational ethics that are already present before our project ever intervenes? And how do we honour these capacities not only in our analyses but also in how we think, feel, and act—during and beyond the lifetime of the research?

Our Methodology

The methodology and a model of our evidence-based mentoring programme will be shared here in 2026.

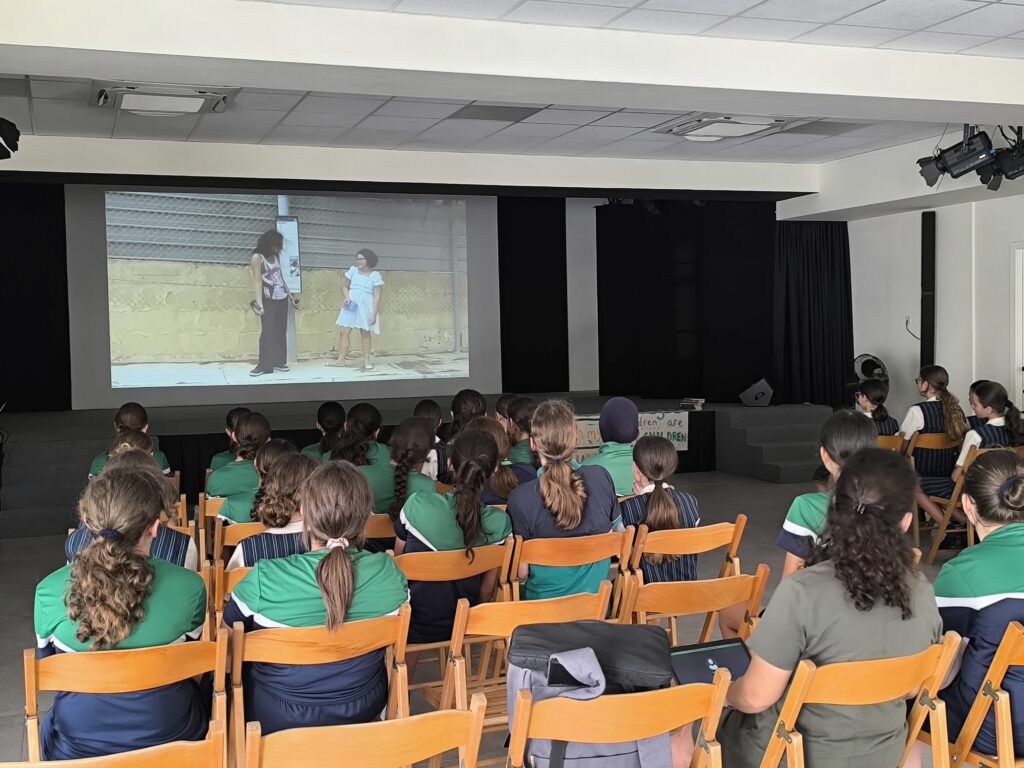

Mentoring programme in pictures

Click on any of the images below to be taken to our Gallery showing examples of our mentoring programme in pictures